By

William Pascucci

It was the early morning on June 6, 1944, in Normandy, France, when the allied armies consisting of land, air and naval forces came together to form the largest amphibious invasion in military history, known as Operation Overlord.

The planning of D-Day in 1944, which was commanded by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, was skillfully planned, executed and deemed a success. Of the 150,000 men who landed that day, more than 10,000 were casualties. D-Day spelled the ultimate defeat of Nazi Germany, which surrendered on May 7, 1945.

Fast-forward 80 years. In the early morning of June 6, 2024, in Normandy France, thousands of people from many nations gathered to honor the heroism those men exhibited during the D-Day invasion. The D-Day 80th Anniversary Commemorative Ceremony at the Normandy American Cemetery at Omaha Beach was truly spectacular and was professionally organized by American Battle Monuments Commission.

In order to assemble the thousands in attendance, along with the protection of hundreds of elected officials and bureaucrats from several nations, the French National Police, National Gendarmerie and local police forces, from Paris to Colleville sur Mer, coordinated restricted travel zones. No one was allowed to travel into or within the restricted zone without a pass or proof of an invitation to the ceremony. Automobile travel to the ceremony was prohibited to most attendees. Invitees were directed to secure staging areas and transported by shuttle buses to the cemetery.

Police were posted at every highway and road entrance leading to the ceremony and travel on highways was forbidden. Access to and from the parking venues was achieved through smaller less travelled country roads.

We were advised to arrive between 6:45 a.m. and 7:30 a.m. at the Bayeux Aventure (amusement park). We began our trip at 6:15 am from Grandcamp Maisy, which was a 25 minute ride. As a result of the road closures and rerouting, we arrived at 7:30 a.m.

Upon arrival, the process of parking vehicles, steering thousands of arriving attendees was surprisingly smooth. It was extremely efficient and it was handled with such organization that it seemed almost impossible that any government bureaucracy would be able to manage the process as well as the French did.

All attendees were screened and then led to the shuttle buses. Buses were line up 4 wide and 3 deep. As soon as one bus was filled it moved from its place forward—another bus behind it filled the void. This process occurred rapidly, and within a very short time, all buses were loaded and we were on our way to the cemetery.

The arrival of buses from many directions converged on the rural roads that lead to the American Cemetery, which caused traffic backups into the venue (although they lasted no more than 30 minutes to 45 minutes). As the buses arrived to the point of disembarkation, people exited them and moved onto the grounds effortlessly. This was all very impressive.

It was at this time we learned that there were at least three classes of ticket holders, green, yellow and white. The most coveted was green, which was held by the D-Day survivors and their immediate families—and perhaps some other high-ranking bureaucrats. The yellow seemed to be reserved for press and news media outlets, while the white was for the majority of those in attendance that day, including us.

As we waited to enter the venue through metal detectors and have our personal possessions searched, we were honored to see the D-Day survivors leave their buses with their families. They crossed right in front of where we waited to enter the cemetery. This was very special and all the veterans received an amazing welcome by those of us who paused to enter the hallowed grounds to honor them this day and their fallen comrades 80 years earlier.

Entry went smoothly and before long we were inside the cemetery and able to roam anywhere on the grounds. We witnessed, live for the first time, rows and rows of thousands of white Lasa marble headstones configured as Latin crosses for Protestants and Catholics and Stars of David for the Jewish interned, all in perfect alignment.

The ceremony began at 11:15 am. In the center of the stage stood a 22-foot-tall bronze sculpture “Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves.” One by one, each of the more than 100 heroic men honored that day were introduced over the public address system. Each received a standing ovation and applause of the entire audience as they were escorted onto the stage. The introductions lasted for 90 minutes. This was an extremely emotional experience and wonderful to have participated.

The official party arrived and included U.S. President Joe Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron and their wives. Once on stage, the national anthems of the French Republic and the United States were played. Next was the invocation, followed by the most unexpected address to all in attendance by Charles Djou, who was a former U.S. congressman from Hawaii and Afghanistan War veteran. Djou was appointed in May 2022 to head the American Battle Monuments Commission. His speech was moving and emotional. To view it, watch the ABMC YouTube channel (https://www.youtube.com/usabmc).

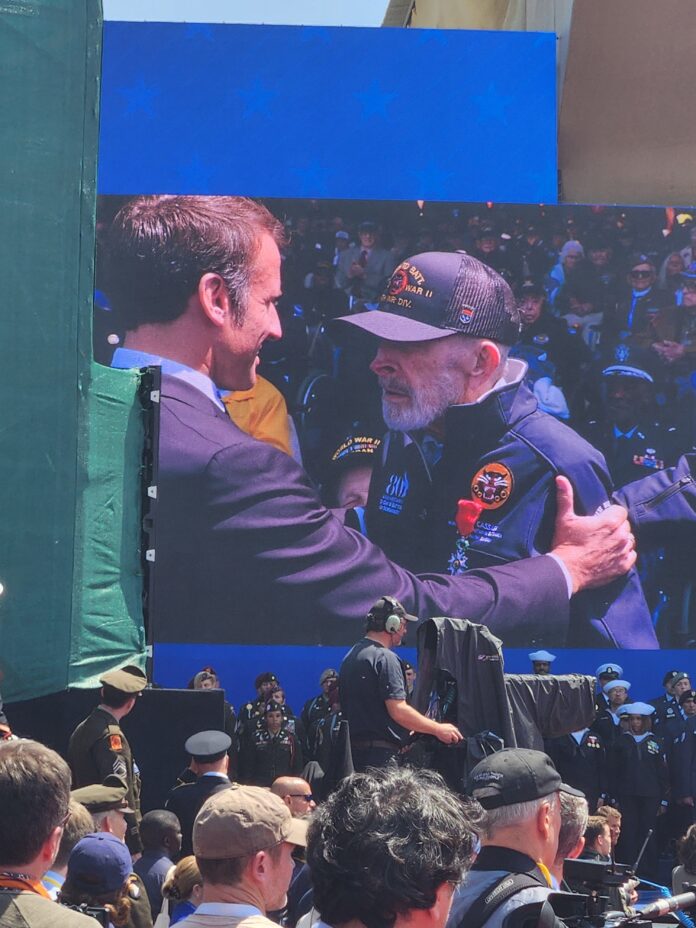

If I thought Charles Djou’s address was special, Macron’s followed that great speech by greeting the crowd in French, and acknowledging each of the 11 veterans by name who would be presented the Légion d’Honneur for heroism shown on D-Day. Before he concluded his remarks, he began speaking in English and thanked the men, who came to fight for France in 1944, and welcomed them ‘home’ today and added, “If I may say.” This was so heartfelt. Macron patiently and ceremoniously stood at attention giving the recipient time to stand and declared the award to each, by name, pinning the medal to their jackets and then kissing each recipient on both cheeks.

The Légion d’Honneur, or Legion of Honor, was instituted in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte. It is the highest civilian award given by the French Republic for outstanding service to France, regardless of the nationality of the recipients.

Biden followed Macron by congratulating each man and handed them a commemorative coin bearing the presidential seal and images of troops on the beaches of Normandy. He addressed the attendees and reviewed tragedies of WW II. He thanked, by name, several of the men on the stage who fought on June 6, 1944.

Biden vowed continued support for Ukraine and warned dictators and bullies not to advance their ambition of conquest on free people of the world. It was a very good address.

At the conclusion of the ceremony, there was a missing man formation flyover followed by Taps and a 21-gun (cannon) salute. All was extremely respectful and well done.

Presuming it was pre-planned, in his final words, Biden indicated that he was staying in Normandy to attend a ceremony at Ponte du Hoc the following day. I do not know if anyone in attendance that day knew exactly how we would all be affected by that decision.

At the conclusion of the ceremony, a U.S. Air Force F-35 fighter jet flew over the entire crowd at an altitude of 500 feet or less at full throttle. It was loud, powerful, and awesome.

As we began to leave for the exits, some strange occurrences began. All exits from the Cemetery were blocked and manned by cemetery staff indicting that no one could leave. This lasted for about 30 minutes to 45 minutes—and some folks were quite upset and voiced their displeasure. Personally, I could not understand what was transpiring. Finally, the blockades were removed and the crowd was released to the general staging area to board busses back to their stations of origin. Lanes were clearly marked, but no access beyond these points was allowed. So, the crowed flowed from the cemetery exits to the parking lot holding area to wait for buses.

The ceremony ended at approximately 2:45 p.m. and it may have been 3:30 p.m. before the crowds made it to the parking lots to meet buses that never arrived. No announcements were made and no reason was provided for the delay. It was sunny, hot and the parking lot was unshaded. During the next two hours, the crowd, having no where to sit and no water or food, began to consolidate by everyone moving closer together. This is still an inexplicable phenomenon to me. Somewhere during the 3rd hour, it appeared that folks in the front of the crowd were leaving the formation, which heightened the enthusiasm of those behind that we could be leaving. This was not the case, but in the excitement, the crowds consolidated even more than before. People were fainting, many were dehydrated and hungry. First responders and U.S. military, along with cemetery staff, began to sparsely hand out water if it was necessary. Some folks were taken away by ambulances for necessary treatment. Still no one left the site.

By 6 p.m., water was being given freely to those waiting for the buses, along with candy bars. There was no explanation provided for the delay or any prognosis for our ability to leave the premises. There were rumors—and the most logical heard was that all roads were closed due to the attendance of the various heads of state in attendance. There were two U.S. helicopters on the grounds that resembled Marine One. I was also told later that there was a 65-vehicle convoy that could be used to transport the various heads of state, but nothing was in motion.

Later, we determined that the various presidents, heads of state and their parties were attending a reception on the grounds with the WW II veterans in attendance. As a result, no access to the cemetery was allowed as French police closed down all roads to preclude the buses from entering the cemetery to take us to our cars.

We began to see a few of the WW II vets wheeled down the driveway from the reception. We later speculated these men had left the reception due to some medical condition or other need. The reception continued.

Around 7 p.m., a few buses arrived. The smallest group from the previously segregated ones was loaded onto buses and left the cemetery. By 8:30 p.m., buses showed up for our group returning to Bayeux Aventure. There were not enough buses for everyone returning, so the staff counted out heads and filled in later. The buses departed and we arrived at Bayeux Aventure by 9 p.m. Luckily we found our rental Citroen 3, that looks like so many others, and departed for the 25-minute ride to Grandcamp Maisy. Due to road closures and deviation, (French for detour), we arrived at home at 11 p.m. All restaurants were closed along the route and in our guest town.

Fortunately, we had some snacks and a bottle of wine waiting. We consumed both and gave thanks to those brave Americans for an extremely memorable day. While it was not ‘The Longest Day,’ it was a long day for sure!