Recently the Denver Post’s Perspective section published an essay by Raf Casert’s essay (“WWI’s Battle of Belleau Wood turning point for United States,” May 27) under an AP byline on the relevance of that battle fought in France a century ago this month. The occasion for Mr. Casert’s article was the planting of an oak sapling (one of a pair), dug from the hallowed soil of the Wood, that was planted on the White House lawn as a symbolic gift to the United States presented by French President Emmanuel Macron and his wife during their state visit back in April.

(The sapling was fated to be dug up the following day to serve time in USDA quarantine. I suppose that because it was French, it was automatically suspect on Trump’s lawn. Actually, foreign plant material is quarantined until shown to be disease free or it is prohibited from entry.)

Mr. Casert also recently visited the Belleau Wood and the nearby Aisne-Marne American Cemetery.

This conjunction of events, coupled with the sorry state of affairs President Trump has fostered with France and our European allies, led Casert to ruminate about the importance of the bitter fight in the Belleau Wood to the rise of the United States to world power at the beginning of the last century.

However, I’m afraid that he has placed a greater burden on this nasty fight, fought 60 miles east of Paris in May and June of 1918, than it can bear. Here’s why.

I realized at the end of the article’s first, long column there was no mention that the young Americans fighting and dying in the Belleau Wood were from the 5th and 6th Marines, forming a Brigade of the U.S. Army’s 2nd Infantry Division or who commanded them or even who commanded the larger American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) of which they were a part (later on Casert identifies Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing as the AEF commander and many of the combatants as marines).

This lack of military detail is really not very surprising since not much time is spent today on military history in the average high school or college U.S. History survey course. If you are not really interested in military history, you probably have to be a marine or ex-marine even to have heard of the Belleau Wood.

Not only military history in general, but public ignorance of the First World War (1914-18), the Great War until the second was rolled out two decades later, is really appalling. Despite the best efforts of the World War One Centennial Commission for the past few years, a minority of Americans probably realize that every day that passes this summer marks the 100th anniversary of some struggle on a Western Front battlefield in which American doughboys, marines and airmen, mostly poorly trained and indifferently equipped, fought desperately alongside French poilu, British tommys, Australian diggers, even Senegalese colonial troops to stem the Kaiserschlacht, the German spring offensive to end the war victoriously for the Reich.

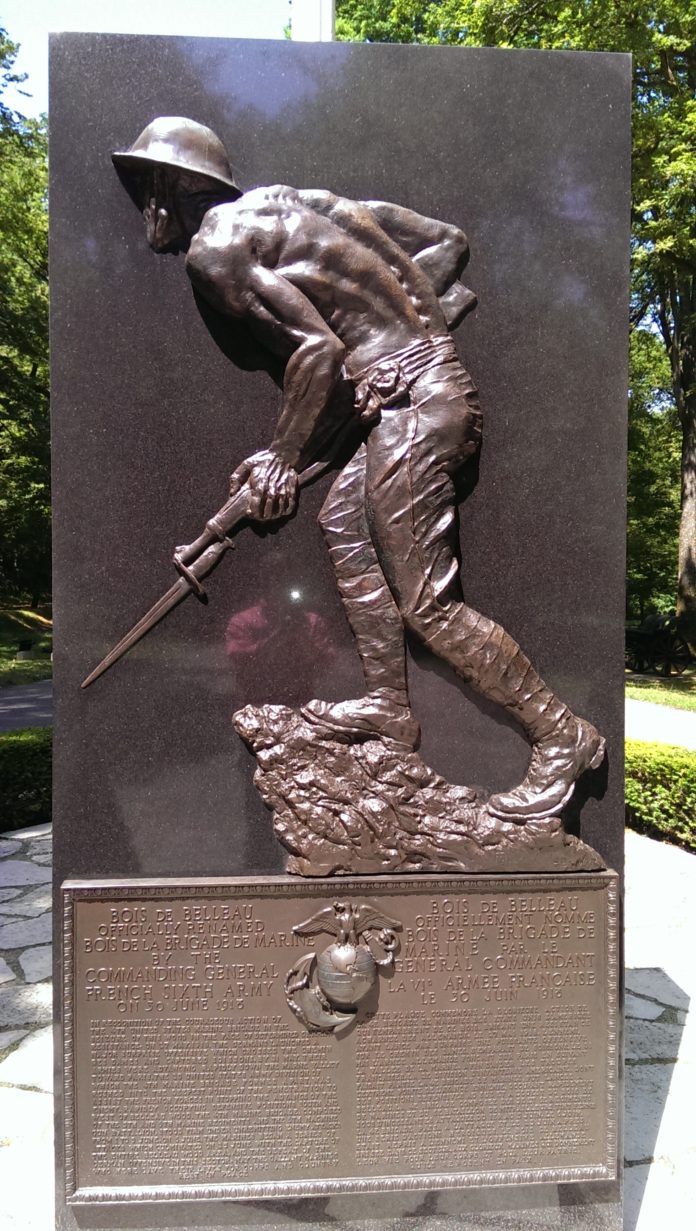

As I write this in June 2018, a century ago the Fourth Marine Brigade was in the midst of epic its three-week fight (one in which it suffered 5,200 casualties, 750 of whom were killed, half its combat strength, also not mentioned by Casert) to capture the unimportant Belleau Wood, a kidney-shaped hunting preserve about a half-mile by two miles in extent, recently occupied by German Soldaten from various units.

But earlier, in late May, the bitter struggle for the Belleau Wood had been preceded by an attack by the 28th Infantry (U.S. 1st Infantry Division) to drive the Hun from the village of Cantigny and by the stand of the U.S. Third Infantry Division along the Marne River at nearby Château-Thierry.

(Since that desperate fight the 3rd Division has proudly born the appellation, “The Marne Division” and the badge 38th Infantry Regiment, then part of the Division, the bears the inscription, “The Rock of the Marne.”)

The real importance of the marines’ fight in the Bois de la Brigade de Marine, as the French renamed the Belleau Wood, and the doughboys’ attacks at Cantigny and Château-Thierry was the fact that they fought the Hun to a standstill and then drove them back, putting to rest the canard that the AEF couldn’t or wouldn’t fight.

The climax to the American military effort came, however, not in the spring, but in the fall when the AEF launched its largest offensive of the war through the Argonne Forest and along the Meuse River. In that climatic battle, American forces suffered over 122,000 casualties, many from the Spanish Flu, a viral disease that passed like a scythe through all the combatants, civilian as well as military, actually killing millions across the entire world.

One hopes that the American media will take special note of the Meuse-Argonne offensive this November 11, formerly Armistice Day, now bastardized into the generic Veterans Day, which contributed so decisively to victory in WWI. More likely, however, the coverage of our mid-term elections five days earlier, with its referendum on the Trump presidency, will smother all interest in commemorating the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the “war to end all wars.”

That neglect will leave the largely unvisited American military cemeteries, monuments and memorials scattered over France (mainly France, although there are American WWI memorials to be found over western Europe from Spain to Scotland) to be again forgotten and left to the careful tending of the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC).

(The monuments in France are largely the efforts of “Black Jack” Pershing, former commander of the AEF and the first head of the ABMC, who saw to it that they were truly monumental and located on the battlefields they were to commemorate, thus far from today’s tourist routes.)

That result will be a shame since those monuments are magnificent stone reminders of the great crusade Americans fought in a century ago to “make the world safe for democracy.”

Mr. Casert’s larger contention — that the Belleau Wood battle first launched the United States on to the world scene in what would become the American Century — is a little suspect. Although the battle is rightly enshrined in Marine Corps lore, the Marine Brigade commander, Army Gen. James G. Harbord’s tactical handling of the battle is suspect. He, like Pershing and most of the American high command, endorsed the tactical concept of “open warfare” that called for infantry to advance against Kraut positions in open formation, pausing to fire their bolt-action rifles before closing on the enemy with fixed bayonets. And, they were to do this in the face of artillery barrages backing up massed German MG 08 water-cooled machine guns, spewing bullets at a rate of 500 per minute. By 1918, after nearly four years of combat, both German storm troopers and Allied infantry were advancing behind intense artillery barrages, showers of hand grenades and automatic rifle fire. And, their attacks were only marginally successful.

Realistically speaking, the Belleau Wood struggle was only one of a long succession of nasty battles whereby the ever-growing AEF, fighting alongside their French and British Commonwealth allies, battered the stubborn Krauts to their breaking point.

While the United States had contributed mightily to the defeat of Imperial Germany, it then squandered the victory when isolationists Senate Republicans, led by Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, defeated the ratification of the Covenant of the League of Nations with its embedded peace treaty. For the next twenty years, the United States abdicated the world leadership position it had won with so much blood, finally to be aroused from its isolationism in 1939 by the outbreak of World War II.

The 40-mile road from the Belleau Wood to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s SHAEF headquarters in the redbrick school building in Reims (now the Lycée Eisenhower with the surrender rooms open to the public), where the Nazis formally surrendered on May 7, 1945, was not as smoothly paved and straight as Mr. Casert would have us believe. But, as he does, we can all hope that the potholes that have appeared in the last year will again be filled, that the two oak saplings will survive quarantine, and that our collective memory of the sacrifices the Western democracies made in both world wars will continue to inspire us.