Fourth in a series

VII

The 16th RCT was scheduled to come ashore at the same hour on the adjacent Easy Red, Fox Green and Fox Red sectors to the east. The earlier combat experience of many of the GIs in the Big Red One was of little help as their landing craft came under heavy fire. The boat carrying the assistant regimental commander and forward HQ personnel was hit off the beach with the loss of all on board. A couple of other boats were swept along the beachfront to touch down on a lightly defended section, taking few casualties. (Apparently the Germans had not manned that Widerstandenester (strongpoint) that morning. Yet, when the regimental commander, Col. George Taylor (who at age 47 found himself crawling across that sandy beach under fire) came ashore around 0800, he found that few survivors of the first waves had made it to the bluff. Reprising what Norman Cota was doing for the 116th RCT, Taylor moved along the line of inert men urging them to cross the exposed beach to the relative shelter of the bluff with the words; “If we are going to die, let’s die up there” and “There are only two kinds of people on this beach: the dead and those about to die. So let’s get the hell out of here!” (Taylor would also be awarded a DSC for his courage that morning.)

And they did. Eventually small groups of GIs, led by unheralded noncoms and junior officers, found their ways up the bluff, engaged the Poles and Russians who made up the bulk of the bunker defenders with flamethrowers, grenades and satchel charges, and took their surrender in growing numbers.

VIII

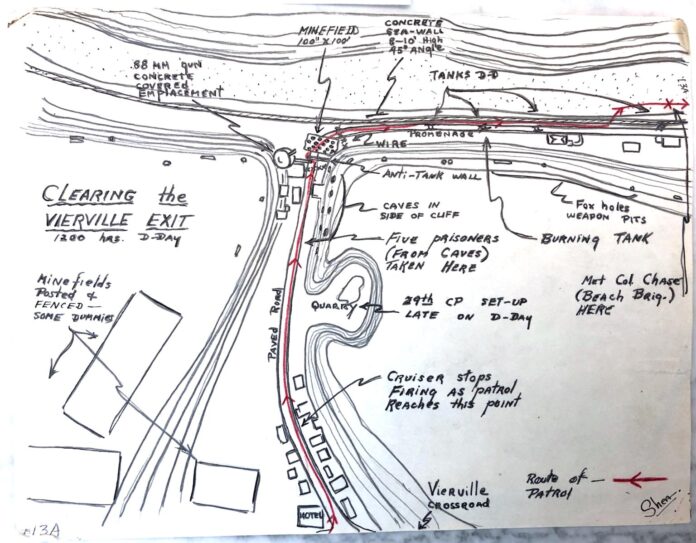

U.S. Rangers from the 2nd and 5th battalions (commanded by Lt. Col. James Earl Rudder, a former Texas A&M football player and reserve officer) were chosen to execute rather overly complicated landings on the western end of Omaha Beach. Rudder personally planned to lead Companies D, E and F of the 2nd Ranger Battalion to attack a powerful casemated battery located on the Pointe du Hoc, a few kilometers west of Charlie Sector. This attack would mean first scaling a 100’ cliff to eliminate the threat from five 155-mm guns that had the range to strike either American beach. Company C was to trail Company A of the 116th RCT, landing slightly west the D-1 (Vierville) draw over Charlie sector; A and B companies were held in reserve so they could land later at the Pointe du Hoc if Rudder signaled that he needed reinforcement. If no word came from Rudder (whose attack was then assumed to have failed) they were to land just west of the draw in order to move overland to attack the Pointe du Hoc from the landward side.

None of this worked out according to plan. As with Company A of the Stonewallers minutes before, Company C was shot to pieces as it came ashore, and the other Rangers following it in at 0645 suffered much the same fate. Of the 68 Rangers of Company C, only 31 made it to the shelter of the cliff; the rest were facedown in the surf or lying wounded or dead on the sand. But, the Rangers weren’t done. The three surviving officers and a couple of sergeants found a sheltered ravine and, using their bayonets as handholds, climbed to the top. Other Rangers soon followed, allowing this small force to attack German bunkers on the west side of the draw from the rear, taking some pressure off the men still on the beach.

XI

Meanwhile, the wind and tide had swept Col. Rudder’s ten-boat flotilla of landing craft (LCAs and DUKWs [duce and a half amphibious trucks]) to the east toward the Pointe-de-la-Percée, about half way between the Pointe-du-Hoc and Charlie Sector. By the time Rudder caught the mistake, one LCA had swamped and the remaining boats and DUKWs, 35-minutes late, were coming in on the wrong side of the Pointe. The Rangers’ bad luck didn’t end there. The DUKWs, carrying extension ladders donated by the London fire service, were unable to navigate the shingle guarding the narrow beach, making it impossible for the Rangers to deploy the ladders. Instead, they fired grappling hooks up the cliff hoping they would hang up on the German wire. Enough did to enable them to rope walk their way to the crest, dodging bullets and potato-masher grenades on the climb. USS Satterlee, standing off the Pointe, did its best to aid the Rangers by firing at the crest with its 20-mm Oerlikons. Communication with the outside world was nil since all radios were lost or inoperable.

After driving the Krauts from the maze of trenches, the Rangers were dismayed to find that the casemates were empty—the cannon had been moved to protect them from the incessant bombing raids. (In the previous 24-hours, some ten kilotons of bombs and 14” shells from the battleship Texas [altogether an atomic bomb’s worth] fell on the Pointe. Later that afternoon, a patrol located the missing guns behind the bombed area and spiked them.) Rudder’s men held on through D-Day until they were relieved on the 7th, despite being reduced to 90 effectives.

Rudder was wounded twice—he had only taken command of the assault after his executive officer, the designated commander, experienced a mental collapse before leaving England. He was awarded the DSC for his actions. A decade later, he revisited the Pointe-de-Hoc with his 14-year-old son, saying at the time that he didn’t see how his Rangers had taken it. But, they had.

XII

At mid-morning further landings on Omaha Beach were suspended. A message from Wilderstandnest 76 stated that the landings on Omaha Beach had been defeated at the waterline: landings had ceased, ten tanks were out of action and ablaze and the beach was strewn with dead and wounded GIs. As late as 1335, the 352nd Division commander, Generalleutnant Dietrich Kraiss, informed Seventy Army HQ that the invasion had been defeated everywhere other than Colleville, which was at that moment being counterattacked. Obscured as it was by the smoke from fires on the bluffs and the usual fog of war, the plight of the GIs on Omaha Beach seemed serious enough for Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, U.S. First Army commander, after conferring with his staff on the command ship Ancon, to seriously to consider withdrawing the troops already ashore and landing follow-up troops on other beaches. He hesitated and, as the situation ashore became clearer, abandoned the idea. (It may have been impossible in any case due to losses of landing craft.) By nightfall, the defenses on Omaha Beach had been shallowly penetrated in more than a dozen places with discrete strongpoints established on top the bluff.

Later, V Corps estimates put the number of D-Day casualties (killed, wounded and missing) at 2,374. Only a 100 of the expected 2,400 tons of supplies had made it ashore on D-Day. Not a single artillery piece was safely landed; 50 tanks had been lost along with dozens of landing craft, including a pair of LCI that were burning where they had grounded at the high tide mark.

Casualties in the 352nd Division ran to 1,200 (killed, wounded & missing), about 20 percent of the division’s strength. With no reinforcements in the offing, it was finished as an effective fighting unit.

The landing on Omaha Beach had succeeded, barely, but the battle to breakout of the Normandy hedgerows was just beginning.