Photos by Regina DeCoster

VIERVILLE-SUR-MER, France—The horror of war created a friendship for two families that has survived after more than 75 years.

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the D-Day invasion in Normandy, France, Houston businessman Jim Trippon, 57, spent several days last week at Chateau Vierville, an ancient building that his father helped to liberate from the Nazis. Trippon visited Jean-Paul Hausermann, whose family has owned the chateau since 1904, to continue the life-long friendship Jim’s father John had with the family.

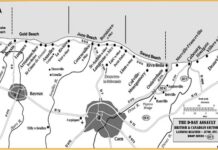

His father, John Trippon, who died in 2014, was a combat engineer and a technical sergeant in the U.S. First Army’s Technical Corps, 6th Engineers Special Brigade, 11 Port of Embarkation unit. On June 6, 1944, he waded ashore with 550 other men in the second wave of troops at Omaha Beach aboard a Higgins landing craft. In the first 90 minutes, more than half of the men in the unit were killed.

The water was only supposed to be a few feet deep, but when the elder Trippon stepped off the landing craft, he and his heavy engineering gear and Browning automatic rifle went to the bottom of a 15-foot hole. “He figured it was a short naval round that made the hole,” Jim Trippon said.

To help get troops off the beach, John sacrificed his body by throwing himself on barbed wire obstacles so other troops could step on him to get over them. The elder Trippon never talked about this incident, or the battle, and the resulting scars on his stomach.

“He never talked about the war until the 70th anniversary,” Jim Trippon said. “All he would ever say about the battle was that he lost a watch given to him during The Great Depression.”

After a full day of fighting, which saw thousands of U.S. soldiers killed and wounded in what was the toughest assignment on D-Day, Jim spent the rest of the night in shallow foxholes on top of the bluffs overlooking Omaha Beach. German mortar and artillery shells rained in all night.

The next day, Trippon and his unit fought their way towards the Chateau Vierville, which is on the top of the bluffs overlooking Omaha Beach. The Chateau, occupied by the Germans as a headquarters since 1941, was a formidable obstacle to the advancing soldiers.

“The Germans had kidnapped a French girl, tore her clothes off, and put her in a medieval tower to entice American soldiers. When they would arrive, machine guns would open up on them,” Jim Trippon said. “My dad saw what was going on and saw a tank arriving. The tank wanted directions to nearby Point du Hoc (where the U.S. Army Rangers landed).”

In exchange for directions from Private Trippon, the tank fired shells into the tower, destroying the German machine gun nests, but unfortunately killing the French girl, Trippon said.

After the battle for the chateau, which left scores of men dead and wounded on both sides, Trippon found a dead cow in a nearby field while foraging for food. He made several trips to the dead animal to bring back fresh beef for other soldiers.

The next day, soldiers from the 29th Infantry Division walked through the same field and were killed by mines, a fact Trippon did not know when he made several trips to the dead cow. During the 75th anniversary of D-Day, more than 100 original U.S. Army vehicles from that era were in a re-enactment camp on the field where Germans planted the land mines.

Hausermann, who was 14 at the time of the invasion and now 90, remembers the landing and the occupying Germans very well. “The commander was a Prussian colonel, who was part of the aristocracy and spoke French. We never saw him again after June 6, he arrived the day before in full dress uniform, warning the family in the chateau to be careful,” he said.

Hausermann said that the overall commander of the Normandy defenses, Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, would visit the chateau to inspect the fortifications in the area. “He would sit at the head of the table in the dining room, while the colonel would sit to the side,” he said.

One of the young captains on the colonel’s staff was part of the famous Messerschmitt aviation family. “One day, my grandmother asked him if he was a Nazi, which he ignored. He came back a few days later to answer the question and said he was studying at Oxford [University] in England and was ordered to report to the army or the Gestapo would kill one of his family members,” Hausermann said.

After the chateau was liberated, fighting continued in the area, including a fierce fight in the small forest behind the house. “Many Americans were killed and wounded there. All seven Germans who defended the woods were killed,” Hausermann said.

He and his family invited the elder Trippon to visit and stay at the chateau many times over the next 70 years. John Trippon, 92, died months after he returned to Normandy one last time in 2014.

To keep the tradition alive, during the 75th anniversary, Hausermann and his wife, Odette, invited Jim Trippon, his sister and children to stay at the chateau, which has a foundation that dates to the 12th century, to commemorate its liberation.

To honor his father, the younger Trippon spent one night on a vintage World War II cot in the same barn John slept in. “It’s a good thing he was out there because like his father, Jim snores loudly,” Hausermann said.